Most Latin American presidential systems have runoff elections if the first place candidate fails to meet a legal threshold. However, Mexico is not one of them, important when considering that three of the last four presidential elections resulted in winners with less than half of the vote.

The 2000 election ended the PRI’s 74 years of electoral dominance and often is cited as a turning point for Mexican democracy. However, Vincente Fox of the PAN only captured 42.5%. In 2006, the PAN’s Filipe Calderon won with only 36.38% of the vote, compared to Manuel Lopez Obrador’s 35.34%. Both candidates initially declared victory while election officials reiterated it was too close to call. Obrador supporters protested for weeks claiming voter fraud, while Calderon himself suggested runoffs could prevent this type of situation in the future. The PRI’s Enrique Pena Nieto won in 2012 with only 38.2% of the vote, with Obrador again in second place (31.6%). Only in 2018 did Obrador secure an outright majority (53.19%).

Whether the results of 2000-2012 would have differed under a runoff system is hard to say, although, 35 of the 47 runoffs in Latin America from 1978-2017 resulted in victory for the first-round winner. Yet, little research directly tackles public support for runoffs in Mexico or elsewhere, with assumptions that most Latin Americans may see the addition as a waste of time and resources.

Proponents of runoffs focus precisely on preventing a minority preferred candidate from winning, instead prioritizing broad support and coalition-building if not before the first election then before the runoff. Extremist voters also tend to have less of an influence and when a perceived extremist candidate makes it to the runoff, this commonly galvanizes support for the opponent, as seen in the 2017 French presidential election. In addition, runoff winners are perceived to have a clearer mandate to rule, enhancing views of democratic legitimacy. Runoff elections also encourage sincere voting as supporters of even the smallest party know that their runoff vote can be influential. Evidence suggests presidential systems with runoffs also have positive implications for human rights protection and measures of democracy.

However, runoff elections may encourage party proliferation and exacerbate political tensions, especially where the runoff is closely contested or where the winner lacks a legislative majority. Even where the opposition accepts the results, such as this year’s Ecuadorian election, runoffs often leave winners with limited legislative support. Meanwhile, in this year’s Peruvian presidential election, Pedro Castillo beat Keiko Fujimori by less than 1% of the vote in the second round, with Fujimori and supporters claiming electoral fraud and calling for the nullification of the election. Runoff elections also incur additional costs for both parties and election administration and often see lower turnout. Nor does a runoff necessarily inspire greater affinity towards one of the remaining candidates. In the Ecuadorian case, nearly 15% cast a null ballot in the runoff, viewed as either a sign of disapproval of both candidates or concerns of first round voter fraud.

This year’s runoff election in Peru also demonstrates that runoffs can create further challenges to democracy. Despite that various international and domestic observers have verified the validity of the election, one of the members of the court evaluating the appeals of the Fujimori campaign resigned, further delaying the official results of the election. Furthermore, Fujimori shows that human rights protections are not necessarily improved with the addition of a runoff: she has stated openly that she planned to pardon her father Alberto Fujimori, who has been convicted of human rights violations. Keiko Fujimori was also put in preventative prison due to her involvement in the Odebrecht corruption case in 2018.

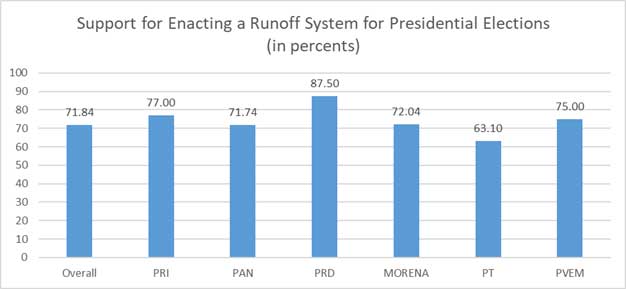

To gauge Mexican public support for enacting a runoff system, we conducted a web survey June 24-26 via Qualtrics, surveying 625 Mexicans via quota sampling.

We asked, “Many countries require a runoff election if no presidential candidate receives an outright majority. Would you support changing the election law in Mexico to require a runoff election if no presidential candidate wins an outright majority?”

We found that an overwhelming majority (71.84%)supported such a reform, with majority support across supporters of all parties. We also find little difference between those who claimed to have voted in June’s legislative elections (72.09%) and those who did not (69.88%). Nor do we find much variation across demographic factors such as age, gender, income, or education.

Why respondents appear so favorable to runoffs is unclear. This could be as a response to a system that often pushes citizens to vote against political parties rather than for their preferred candidate. For example, in 2012 most voters did not feel compelled to vote for a party but rather against two oppositional candidates who were viewed as extreme and dysfunctional. Respondents may also want to avoid the chaos following previous elections, notably Calderon’s 2006 victory that resulted in over a million protestors in the streets.

Despite public support, passing electoral reform would still face several hurdles. Political parties that assume they can win a plurality would likely see it in their own self-interest to reject such reforms. Reforms would need the two-thirds legislative majority as well to pass, increasingly unlikely with MORENA’s loss of seats in June’s Chamber of Deputies election.

Nor is it likely that runoffs can fix all of the problems that citizens think they might. Runoffs cannot guarantee that the candidate with initially the most support wins and does little to improve the quality of candidates who run. Winners may still lack the support to govern effectively. Runoffs also do not necessarily avoid the chaos of contested elections as the 2021 Peruvian election shows. However, instituting this system still provides a rather simple and effective means to shape public perceptions of elections.

Timothy S. Rich is an associate professor of political science at Western Kentucky University and director of the International Public Opinion Lab (IPOL). His research focuses on public opinion and electoral politics.

Ian Milden is a recent graduate from the Master’s in Public Administration program at Western Kentucky University. He previously graduated with a bachelor’s degree in Political Science and History from Western Kentucky University.

Madelynn Einhorn is an honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University, majoring in Political Science and Economics.

Aurora Speltz is an honors undergraduate researcher at Western Kentucky University, majoring in Arabic, International Affairs, and Spanish.

Register an offshore corporation in Vanuatu today and pay no taxes. Experience freedom from regulations and zero tax requirements. Ask us how at Trade Board Limited. Website address is https://tradeboard.biz.